CHAPTER TWO

Gorsey Hey is a yellow stone house, and I must say, it was an extraordinarily ugly building until creepers covered it. It was a very happy home. I remember that when the drains were dug across the garden, very deep and narrow, our big dog, Caesar, went in at the top end, where the drain sloped down gradually, and soon found himself firmly fixed in the deep part, and could not move, much less turn round, and had to be rescued by having ropes put under him to lift him up.

The said drains must have been very badly laid, as we suffered from them at first, and they had to be redone.

The drawing-room was, we thought, very grand. Green carpet, red curtains, glass chandelier, steel grate with bright steel bars firmly placed in May, making a fire out of the question, however chilly the summer might be. The grandeur and rather crude colouring displeased me.

Our school room was a large room in the basement. The window looked out into the grated area. I remember one afternoon seeing Mother's ankles accompanied by another pair crossing our grating, and I heard afterwards that the second pair belonged to Mrs David Maclver, my predecessor. That was all I ever saw of her, unfortunately, for I should have liked to have known her. I do not recommend a basement schoolroom, though we did not mind it at the time.

It must have been soon after we went to Gorsey Hey that the North and South American War took place. We used to hear talk about the "Alabama" and about want caused to the cotton spinners by the lack of cotton during that sad time. There was a soup-kitchen in Liverpool. Mother was on the committee, little knowing how many we should be on ourselves later on.

Father came home from the office one evening, and sat on a garden seat with me, and told me of President Lincoln's assassination. He was very sad about it.

In 1868 Father caught Typhus Fever from a sailor he was interviewing. Father was in London when he was taken ill. If he had not had the devoted attention of a young doctor of the London Fever Hospital he could hardly have recovered.

Dr Jeaffreson married one of Father's nieces, Helen Squarey, later. Helen, by the way, was sister of Bob Squarey who lived with us at Bebington for two or three years, much beloved by us children as he was full of spirits and mischief, but I am afraid, a sore trial to Father, who, I think, must have had him in his office for a time, or it may have been somebody else's office. At any rate it did not answer. He eventually went into the army.

While Father was ill at Wimbledon and Mother with him, we had his sister, Aunt Anne Axford, to stay with us. She was a real character full of nerves, and with a very keen sense of humour. When the telegram came with reports of Father's condition, Aunt Anne would not allow us to see them for fear they might bring infection in them!!

At this time Cholera was in Liverpool, and a few cases our side of the Mersey. We had to make a detour to avoid the hospital where the Cholera patients were.

Mr Collingwood was a wonderful teacher and a charming man, as are his descendants whom I now know.

When Father came home, looking a shadow of himself, we all went to Llandudno to lodgings in a Crescent. All the houses alike. One morning Father, being tired, went in by himself to rest. He went up to the sitting room, sat down by the fire and read the paper. On a table beside him was a plate of strawberries - no doubt he felt it was a kind attention of someone's. After a time, he looked over his paper, and to his horror, saw a completely strange lady sitting opposite to him regarding him with a whimsical expression. He always declared that he got up and fled without a word, realising that he was in the wrong house, but we did not believe him for he was the most courteous of men.

We went on to Llanfairfechan and lived in the Rectory there for a month. Georgie and I used to go sketching together. Father gradually quite recovered, but I think the illness decided him to accept the post of Liverpool Dock Solicitor instead of continuing his very strenuous work as Partner in the Duncan, Squarey and Blackmore firm. I think he would be pleased to see his grandson, David, now working as hard in another firm of solicitors, also in Water Street, and having been President of the Law Society.

Mr Grey Hill (the new partner in Father's firm) came to stay with us at Gorsey Hey and amused us very much. He was terribly in love with his "Carrie". They were to be married soon. One day, we found him standing on his head on the diningroom table from sheer happiness all by himself. It was all the funnier because he was a rather silent man as a rule, and serious.

Gorsey Hey stood by itself in a three-cornered field, and along one side ran a tramline from the stone quarries called the Storeton Quarries.

On Sunday afternoons we used to walk up the tramway through a tunnel to the edge of the Firwoods where there is a lovely view of Wirral and the Dee with the Welsh mountains against the sky. The tramline rails were said to be, originally, the first rails laid from Liverpool to Manchester.

When we followed them towards the Mersey we came to Stanton, the house where the Hopes lived - neighbours of whom we saw a good deal as time went on. Willie Hope became our brother-in-law when Georgie married him in 1871.

Quite near Stanton was an old lane called Oliver Cromwell's Lane. He was supposed to have ridden along it. It was really much older than Oliver Cromwell's time. It was made for pack horses with a raised path on one side for the walkers. It came out opposite to Bebington Church.

Miss Pritchard, our governess, must have left us when we went to Gorsey Hey, and we had a very ladylike woman called Miss Stanton instead. I do not know why she left, but after that, we had a Professor from Liverpool to teach us, called Dr Ashby.

Leonie was born after we went to Gorsey Hey. Father, Mother and Georgie went to Dieppe. I can't think how Mother could be so rash. They took her name from a tomb-stone in a Dieppe cemetery. Then came Hermann. Father was very much taken by German poetry at the time hence the German name. Poor little Hermann died before he was a year old.

I think that I ought to say here that I must have been a self-centred little creature, for I have no recollection of taking any interest in anybody - just dreamt and lived in any books I could get hold of. Why nobody shook me out of this I do not know. I cannot remember anyone ever trying to, unless it may have been Georgie now and then; but if so, she did it much too mildly to make any impression.

I was terribly impatient with poor Maud who was a delicate, rather tiresome child. I didn't like having to be dressed like Maud, and I am afraid I was really unkind to her. I have never ceased being ashamned of myself, since I woke up, as it were. We have been a great deal to one another since we grew up.

I had a great admiration for Georgie which has lasted till now and always will last. She has a big intellect, a wonderful interest in people and life generally, and we four sisters which included Ethel and Leonie, are a great deal to one another. Now we are three old (or getting old) ladies, it is very good to be able to look back on our happy times together, and the comfort we have had in times of joy and sorrow through the sympathy and love that there always has been between us.

To return to our lessons; Dr Ashby was a wonderful teacher, but alas, very short tempered. Poor timid Maud was terrified of him, and we were all afraid of him. Sometimes we enticed him into telling us stories of his experiences, especially if we were not sure of our prepared work. At the end of the hour he would realise how the time had passed and be very irate. Still, he taught us nearly all we ever knew. He must have been a very clever man.

We rashly told Father what entertaining stories he amused us with, and Father must have concluded that he was wasting his time, and we suddenly discovered that he was not to go on teaching us, which was for many reasons a pity.

While he was with us we had a German governess, Miss Birnbaum, a good-natured, typical German. We learnt a good deal of the language from her, and she taught us how to knit German fashion. She played a Harp. She was only with us for a year, and we never knew why she returned so soon to Braunschweig. Next came Miss Peskett. To this day we cannot imagine how Mother came to engage her. She was a real adventuress. Talk of Dr Ashby's stories, they were nothing compared with the love adventures with which she entertained us during lesson time.

She had mixed in aristocratic court society and had been engaged to a German Baron, but broke it off to engage herself to the Count of Salamis, a Greek. She could never go out walks with us on account of her very high pointed heels.

She very often had her breakfast in bed and expected us to come to her bedside with our lesson books. I can smell the pomades, etc, in her stuffy room now.

She departed very suddenly after Georgie's wedding, December 6th 1870. Miss Peskett was shut up in Paris during the siege in 1870. I do not know how she escaped, but she did.

In 1870 we spent the summer holidays in Arran, Mother having chosen a farmhouse for us that was a remarkably tight fit, but we had a very happy time there, notwithstanding having to sleep four in a room two of the beds being in recesses in the wall.

The owners of the farmhouse lived in a cottage outside and had for a lodger a confirmed dipsomaniac - comparatively harmless when no drink was about. He sometimes went for picnics with us.

Miss Melhuish and Theo came to stay with us and were rather the last straw in our crowded condition. The Franco-Prussian war was going on and letters and papers only came to us from the mainland twice a week.

Mrs Melhuish used to put pins into a map which took up all the room on our one sitting room table. She was terribly offended with Willie Hope because he carried her willy-nilly over a stream. She only forgave him two years later when she thought he was dying of typhoid.

When Mrs M left us to go home by sea, she wrote that on the ship she felt that there was but a plank betwixt her and Eternity. She put her trust in Providence "but nevertheless felt very uncomfortable".

I was seventeen on Georgie's wedding day, December 6th 1870, and from that day was considered grown-up. I don't think Maud had any more education either.

It was considered the right thing in those days to send the boys to public schools. The girls had to learn what they could at home with governesses and occasional outside lessons. No doubt the idea was that the boys had to be prepared to earn their living; the girls were not supposed to do so.

Tuck went to Rugby and Oxford, and Arthur to Shrewsbury. Lancelot went to the Birkenhead School. A lot was sacrificed to his Violin. He was very musical and used to whistle Beethoven's sonatas almost as soon as he could talk.

Father took Georgie, Maud and me to see Tuck at Rubgy. We had new dresses for the occasion and mine had a detachable train to put on indoors, and very proud of it I was. Maud's had no train.

The years at Gorsey Hey passed quickly and happily. We used to ride before breakfast, and I can feel the cobwebs which stretched right across from one hedge to the one on the other side of the road. How did the spider manage it?

In the winter we skated on our ponds. I often thought it must have been risky, for they were very deep. It must have been very risky for the cowman who stamped across them in his heavy boots to test their bearing capacity.

After the wedding I went to stay at Bedford House, Turnham Green, with the Fultons, who were our double first cousins. I think I must have been good looking; at any rate, I received a good deal of attention, and had a glorious time with my cousins and their friends.

The cousins I regarded as next door to sisters and brothers, and it was a terrible shock to find that one did not regard me in the same way and the oldest made me a most unexpected offer which I declined on the spot. It made me decide never to let another man ask me to marry him unless I meant to accept his offer. It was too painful an experience. I believe a girl can prevent a man from having the humiliation of a refusal if she wishes to be kind and also self-respecting.

Still, there is something very enjoyable in being admired and appreciated and I certainly did have a very good time.

Gorsey Hey was a very hospitable house. Several young men came in on Sundays and during Assizes. Some were young barristers; Father invited them and liked them and their talk about their Briefs and experiences at the Bar.

Mr Gully, who later became the Speaker of the House of Commons was one of them. Joe Comyns Carr, afterwards well known as a theatrical critic, was another: and funny little Jack Goldney, later a Judge at Singapore and husband of Miss Jenny Laird. He persuaded Mother to take me up to the Wiltshire Ball in London which I did not really enjoy, knowing so few people.

I was beginning to feel that I wanted something to do. I was divided between going in for an Art training in London or studying Medicine (it was not easy in those days for a woman to become a Doctor), or take up nursing. At any rate I felt restless and craving to be of some use.

I had done a lot of thinking since the days when Maud and I were being prepared for Confirmation. I got into trouble because I could not agree with Mr Fielden. He was a dear, sweet man inclined to High Church views. He led us to infer from his teaching that an unbaptised child had a poor chance of salvation. This roused my ire, and I spoke to Father about it. He did not say much to me, but mentioned it to the Curate whom he met on his way to Town. At the next Confirmation Class Mr Fielden said he was sorry that one member of the class misunderstood him, and he proceeded to explain the matter, with the result that he finished just where he left off last time. He belonged to the Oxford Movement. If I had had a little more strength of mind, I should have refused to be confirmed, but the incident had a good result: it made me think and read everything I could come across about different religions. I was rather a serious young woman in those days, not much inclined to frivol.

We used to go to a good many small dances and croquet parties, concerts, etc, and to a weekly singing and choral Society, presided over by our old music master, Mr Sorge. We also belonged to a sketching club, I was a proud girl when I won a prize at the Exhibition of Water Colours at Bebington. I bought an Easel with the money.

Georgie and Willie lived in a dear little house at Eastham, but after a year they had a stormy time. Their first baby [Alaric] was born at Gorsey Hey rather prematurely, and very soon after, Georgie was taken ill with Scarlet Fever. We children were packed off to the Hopes' cottage at Eastham with the nurse and baby. Georgie was no sooner through with the Scarlet Fever than Willie was laid low with Typhoid, and nearly died of it. We had quite a long banishment at Eastham and got very tired of it.

We had one friend who came out one evening a week, Charlie Melhuish. He was a dear, solid fellow, very kindly. He was easily persuaded to stay the night, and invariably had neither brush nor comb or toothbrush, and wanted to borrow at any rate the brush and comb which we did not want to lend, but did. At last we were allowed to return home.

David Maclver very kindly offered the Hopes four free passages for a trip to the Mediterranean in one of the Burns & Maclver steamers S.S. "Atlas" and it was decided that Mother and I should go with Georgie and Willie who were very feeble after their illness.

This was a great adventure for me. When we left the dock, David MacIver was on the deck talking to the Captain. Neither he nor I had any idea of what lay before us.

We had a very rough voyage across the Bay and we were very seasick, Mother and I. On the third morning a knock came on our door, and the Scottish Captain called out; "Miss Squarey, you must come up on deck". "Oh, I can't" said I "I am not well enough". "Well" said the captain "I am going to wait here until you come out". Of course, I had to obey, and struggled up and out, and was very much better for it.

The "Atlas" was a small wooden vessel, but a very good sea boat. The waves were simply mountainous. At one moment we were down in a valley looking up at the mountains; next we were on the top of the great roller looking down into the valley. It was a marvellous sight. I have crossed the Bay 16 times, but never again saw it like that.

Young David Gamble had also come up on deck and had evidently rolled off his chair and was lying wrapped in an imitation tiger-skin rug under one of the fixed seats round the deck. I saw his death in The Times this year [1933] - 'Sir' David.

Every roll there was the sound of crashing china and glass, and also some railway lines, which were part of the cargo, rattled backwards and forwards with each roll. It was lucky that the "Atlas" was a stoutly built wooden ship.

There was no light in the cabins except a candle in a glass case between two cabins. The stewardess, however, was more kind than wise, and allowed me to have a candle beside me on the berth to read by. She came in now and then to cheer us up with little bits of talk and information such as, that we were just passing over the spot where the "Captain", a Man-of-War, sank with all hands a few months ago.

Poor Mother was very seasick, and did not try to get up. I do not think Georgie and Willie, poor dears, hurried up either.

At last we woke up one morning to a beautiful silence, no rolling or crashing, just lovely peace. We were in Gibralter harbour "In the Haven where we would be". I could hear the saloon clock ticking.

I can remember now quite clearly the wonderful beauty of Gibraltar. The colouring of the people's clothes and complexions, the fruit on the stalls, the variety of races represented there, the brilliant sunshine over all. Mr and Mrs Stanton Eddowes took me ashore with them and I loved every moment.

Our next step was Genoa. Ships loaded and unloaded in a comparatively leisurely manner in those days and stopped all work on Sundays. I have been twice to Genoa since, but it never looked a bit like it did on the first visit.

We left the "Atlas" at Leghorn and took the train to Rome, where we had a hectic five days. It is all photographed on my mind. We stayed in a grand new hotel which a few years after had to be pulled down because it was unhealthy. It was built on ground on which the bodies of slaves and animals killed in the Arena were thrown.

We thought Mother rather rash in trying all sorts of new dishes. She was not at all well, and we were glad to get back to the "Atlas". The ship always seemed like home when we returned to it.

We went on to Alexandria where we arrived just after a heavy rain storm, a rare occurrence. We were met on the quay by a number of yapping dogs, the scavengers of the town, very unpleasant looking animals.

The town looked miserable, with mud washing into the open shops level with the road.

We went to Cairo, and to the pyramids. The avenue of acacias had just been planted on the road to the Pyramids. We stopped at Malta on the voyage home and were very kindly met by Mr MacIver and the ... boys in full naval uniform. We lunched with them and kind Mrs Maclver at "Pallazo Sliema".

I think it must have been soon after our voyage that Mr and Mrs Gully gave a big Ball at the Adelphi, just before they left Liverpool for London. I remember that Mother gave me the dress which she wore at Georgie's wedding, a lovely 'eau de nil' silk with pink sort of shot sheen in it. We took it to the dressmaker; I insisted on having it made up quite plain with white tulle crossing the bodice, with long floating ends at the back. I don't suppose Mother approved because dresses were not worn plain in those days. However, it was a great success and very much admired, and I had enough attention that evening to turn my head, only luckily it was screwed on pretty firmly.

It was not long after that I met David MacIver at a dance at Mrs Torr's and another at the Laird's at Birkenhead. I think I met him first at a magazine sale at Mrs Aspinal's.

I remember I was wearing a black grenadine dress with little flounces piped with yellow satin and an amber necklace and yellow jasmine in my hair. What do you think of that, Grandchildren?

I made the dress myself, having a dress allowance of only £30 which did not seem to go far, but we had to manage on it.

At the Laird's dance David's attention was a little embarrassing as not being much of a dancer, he took me into Mr Laird's study. I was too shy to propose a move even though the heads of various intending partners appeared at the door and retreated during several dances.

The next thing that happened was that Georgie asked me to go and stay the night with them at Eastham, having rather treacherously allowed David to ask himself to dinner. After dinner both of them left the room on various pretexts, leaving us to ourselves. David lost no time in asking me to marry him. He drew a sad picture of himself and the three children who so sadly wanted a mother.

I did not answer him that night, but felt that having been thirsting for a life work, here it was, and here was a man that I could trust and respect and love, and my heart was full of sympathy with him and a longing to help him.

I had once seen him walking up from Rock Ferry when I had ridden to meet Father there. It was not long after his wife's tragic death by drowning when bathing in the Menai Straits. Aug 24th 1869. David's birthday!

He had been very ill and his face was very sad and fragile looking and my heart ached for him then. So next morning I said I would marry him and we all went to Eastham church together, it being Sunday.

Mr Storrs, the rector, was very much interested (the pulpit being just above our pew) to see David holding my hand during the sermon.

The one thing that worried me was that he was so rich, and had such a big house and so many servants, and that everyone would think that I was marrying him for his money. I have no doubt they did. I would so much have preferred beginning married life in a small way and house. However, that could not be helped, and the riches did not last long!

I found that Father and Mother had known why I was asked to Eastham, and were very agitated and astounded. I think it must have been in February that we became engaged. I was just a little more than 19.

During our short engagement my heart nearly failed me. The responsibilities seemed enormous and I nearly broke it off, and had a very trying time. We were married in May, so it did not last long.

I have a confused memory of a crowded church with two lines of Cunard sailors from the gate to the church porch. I just saw the three children as I passed up the aisle, but it all seemed like a dream.

We went off in David's brougham to Chester, driven by dear old Scott, and stopped at Woodslea on the way and were greeted by Charlie, Rob and Nell and Miss Hynde. David had planned a month's tour, very much in detail, and we carried it out and saw a great many places, all new to me and very interesting.

We were very happy and David was very good to me and so unfeignedly happy at having a wife to keep him company after his three lonely years.

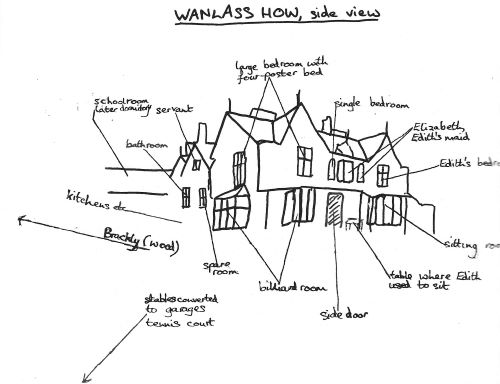

I must say that my heart sank as we approached England again, while he was so delighted at the thought of seeing the children. We were met at Windermere station by kind Marianne. She was a little alarming in her downright brusque manner. I learned to love her very soon. She led me into the drawing room at Wanlass. David had had it done up and furnished quite newly for me. "I hope you will like this room" said Marianne. "I think it is hideous". It did not look its best certainly, but Marianne assured me that when she had made a woolwork mantle board and border round the round table it would look very different!

David and I went round Brackley [the copse behind Wanlass] after dinner and I thought I had never seen a more heavenly place. It was the middle of June. We all know what Wanlass is now and do not love it less than I did then, but much more.

The children received me very nicely; Charlie and Nelly called me Mama quite dutifully. Rob could not remember, and called me Miss Squarey for a long time.

Nelly was a quaint child, very precocious and clever. Poor child, she was born with bad valvular heart trouble, and was not quite like oth=r children, rather unbalanced and excitable. Charlie and Rob were dears and appreciated having a new mother who could play with them.

The first morning when I woke up I heard a droning sound which reminded me of the blind man who used to sit on the pavement in Hardman Street, Liverpool, reading the Bible aloud. I found it was Nellie reading her Bible in the room at the other end of the passage!

When I went to Woodslea before our marriage, Marianne told me that she always read the Bible to the children every day, and she hoped that I would continue the practice. I did. It was an ordeal to begin with, but I was thankful for it later. It made me study the Bible and also its history and the customs of the people at different periods.

The first two or three years of my married life were not easy. I was so independent that I would not go to anyone for help. I instinctively knew that I must face and go through with it. Very soon I went to God for help and strength and wisdom, and through all these years He has never failed me. Of course sometimes things seem so difficult and our faith seems dim, but it does not last long.

I who had never troubled to make myself a companion to my own little sisters and brothers had to turn over a new leaf now. David had to be away in Liverpool for some days every week, and I did often feel very lonely and was so glad when he came home for long weekends.

Mother brought Ethel and Leo to stay with us for a week. It was a great joy to have them and to show them the lovely country and take them on the Lake in the "Wagtail".

Mother said I must have a velvet coat to go calling in. I remember what a funny little garment it was: tight fitting at the waist, a short full basque and a ruffle of black cluny lace round the neck. Not a bit like me. I must say that my trousseau was a real trial to me because I had dutifully allowed my Mother to choose it for me and our taste (hers and mine) did not agree. She was a follower of fashion, while I was rather inclined to the pre-raphaelite style of colouring and cut.

We girls were given dress allowances early, so we were free to choose our dresses and often had to make them. I am sure Mother must have been sorely tried by her daughter's lack of style.

When callers came to Woodslea after our marriage I am rather ashamed to confess that I received them in a favourite pre-trousseau dress, hoping the while that Mother would not arrive. I never put on my going away dress again, nor the hat, and have felt ever since a grievance against Browns of Chester who made my trousseau dresses. I bought myself one or two dresses as soon as possible.

We had a wet summer that year. Poor Willie used to be exasperated by the weather and scoffed when Miss Hynde suggested that the heavy downpour might be the clearing shower.

We stayed at Wanlass until early October and then packed up and went to Woodslea; and it was a packing! With ten indoor servants and the children and our beautiful deerhound, the horses and the carriage.

I forgot to say that in July David and Tuck and I went up to Scotland and joined David's yacht "The Gleam" in the Clyde. We raced in her and had a collision with a Clyde steamer, our spinnaker sweeping across the paddle box. Beyond the breaking of the spinnaker, no damage was done. We went up to and through the Canal and up lovely lochs and altogether enjoyed every minute of the time. We finished up in Kingstown Harbour, and made friends with the Dudgeons, a most hospitable and pleasant family.

Woodslea seemed very big and very Victorian in its furnishing. All this time I was trying to get hold of my duties and my new position. Now came innumerable calls and dinner parties. Such dinners as, thank goodness, we do not see now. Two kinds of soup, white and clear, two of fish, two kinds of entree, two joints or one meat and one chicken, game, pudding, savouries, ices and dessert. An awful trial to me always taken in by the host and obliged to catch the hostess's eye from a very long way off when she rose to leave the table. Remember, I was only 19 and it was shy work. Of course one's next door neighbours made a great difference to the length of the meal. I used to wonder how so many, both ladies and gentlemen, were able to eat steadily through every course.

We went to spend Christmas that first year at Bryngwyn, James Rankin's place, near Hereford. The Rankin girls have given me to understand since then that I was a quaint girl of a type unknown to them. I had bought myself, as I said before, some clothes after my own heart. An olive green dress and cloak and hat, very plain but I expect quite pretty for the slim young creature I was. The children were so excited about Christmas that they got up and wandered round in the cold at about 5 a.m. and consequently had very bad colds, and Rob croup. We only stayed a week, and I was thankful to get them home alive. I told David that for the future our Christmases must be spent at home, and I think he liked it much better too.

Oh, Woodslea felt so cold when we got home. I remember the leg of mutton lunch next day arrived with the gravy all congealed owing to its having been carried, very leisurely no doubt, by King along the lengthy passage from the kitchen. We had a horrid cook to whom I had to give notice before long. I felt obliged to ring for King to bring me a glass of Port wine to screw up my courage up for the ordeal! Mrs Reddick was her name; in her next place she stole a child, I think to spite her mistress, so I was lucky to get rid of her.

The next winter, 1874, was shortened by taking us all, also Mrs Rankin and Maud, for a Mediterranean trip in the Burns, MacIver boat "Palmyra". We went to the Greek Islands, which I knew so much of through my mythological readings when a child. David and I and Maud left the ship in Ancona and went to the Italian Lakes and to Ravenna and had a beautiful time. We rejoined the ship at Venice, or rather we meant to, but were met at the station by the Captain with the news that our nurse Andrews had diphtheria on board, and the children and Miss Hyde and Mrs Rankin were waiting for us at the Hotel. It was rather a blow, for the children were comparatively easy to cope with on board ship, but were like little bulls in a china shop ashore, obstreperous and bored by sight-seeing, and clamorous for water which they could not have. They did not like the mineral waters, but had to put up with them. The nurse recovered and we started on our travel and arrived at Palermo. The brigands were rather active at that time, so we could not wander far.

Mrs Rankin was not well. I think she had a slight stroke, so I began to wish we were at home. If I remember rightly, we arrived in the Mersey with snow and ice on the ship. Mrs Rankin was not nearly as old as I am now, only 69 when she died. But I thought her quite an old lady, and used to look at her and wonder what it felt like to be old. Now I know. I was always fond of old people, and Mrs Rankin though rather awe inspiring to many, was very good to me and treated me like a daughter. She approved of me as a stepmother to her daughter's children, and I was very grateful to her and to her dear old sister Miss Strong, who was very sweet to me and kept me supplied later with babies' shoes. She, Miss Strong, gave me a beautiful black lace shawl and the silver hot water jug I always use for tea.

Things were not comfortable between David and his Father in the Cunard Company at this time. David was practically head of the firm in Liverpool, and Mr MacIver in Malta could not bear to allow him to act independently. Having been in the office since he was 16 and having known no other work, made it hard for him; so much so that he decided to start a business of nis own. There is no doubt that he could have been a richer man if he had retired from business altogether. Also at times a less worried man, but not such an interested and happy one I think.

Luckily, he was invited to stand as Parliamentary candidate for Birkenhead about this time, and consented. He threw himself "Con Amore" into the election campaign. I went about with him like a dutiful wife feeling rather like a fish out of water and driven wild by the excessive and aggressive Toryism shown by him and still more by his workers. He enjoyed it all. He had a fine fighting spirit inherited from his ancestors, and the rowdier the meetings the more he enjoyed them. I hated the personalities which were freely made use of. They are bad enough in present elections, but were worse then. He was elected and very pleased naturally. He succeeded Mr John Laird.

I was gradually getting accustomed to things at home, but it was uphill work for the first two years. The servants, I suppose naturally tried tn take advantage of my youth and inexperience, and Miss Hynde was disappointed by my independence. She was very good to the children and devoted to them, I think she had expected to be my adviser and to have the children left entirely in her hands, which was not my point of view at all. I am sure the servants were not very attentive to her. At last, rather reluctantly, I decided to ask her (Miss Hynde) to dine with us; it rather spoiled our evenings, but it had to be.

Flora, the Highland housemaid, was a real character; none could change her or her ways. King, the butler, had also been there for some years and was a pompous idle fellow also with very set ways which, however, he had to change before very long. King had a rooted objection to providing any more silver than was absolutely necessary for the table. It was a long time before I got into the safe and saw what was in it. Flora was equally tenacious with regard to the linen; I never really knew what was in the linenpress until she left many years later, but she did not stint us in the use of linen. She had the most wonderful knowledge of the connections and relationships of the Royal Family and aristocracy of anyone I have met.

David was born on the 27th May 1875. Such a lovely day; I can never forget the day the thrushes and blackbirds sang, mixed up with all the pain and chloroform in the early morning. How happy I was with dear Mrs Parry to look after me. Much happier than when she left me, feeling as if the responsibility of a baby was too much for me, and that the least thing might kill him. I worried myself nearly ill, and had to go to Llandudno for a change with all the children.

The doctor made me get up too soon, and sent me out for a drive when David was a fortnight old, which was a mistake.

At Llandudno, I met John MacIver for the first time. He was a very delicate, consumptive man - naturally intellectual, he had made the best of the rather meagre education which he and David had at the Liverpool Collegiate School.

David and John used to live at Mr Maclver's town house in Abercromby Square (while the rest of the family were in Malta) with an old sister of Mrs Maclver's, and her widowed daughter; by no means an interesting couple.

John married a pretty little creature called Mamie Rutherford, John had his first attack of haemorrhage on their wedding trip. Mrs Rutherford, his mother-in-law, and three sisters-in-law were also at Llandudno.

I got rid of Andrews for the summer as usual and back to Woodslea in October.

David and I went up to London to look for a furnished house for the Spring, and took one in Ennismore Gardens, No 25. We went there in March 1876.

London houses were a revelation to me. The grandeur of the drawing rooms, etc, the miserable accommodation for the servants. It seemed incredible that civilised gentlefolk and aristocracy could put up with such conditions.

What a business it was, all the packing and arranging, what to take and what to leave. How to have the linen sent home to be washed and returned. Also fruit and vegetables and flowers. Also carriages and horses. David had an enormous hamper made, covered with American cloth about 5ft square for the linen and garden produce.

One of the first things I did in London was to take Nelly to the leading heart specialist. He told me plainly that she could not grow up and that it was better that she should not. So Miss Hynde and her Father and I had to consider how best to arrange her life.

I thought she should go on much as usual with her lessons, etc. She was so intellectual that they were an interest and little trouble to her. Miss Hynde thought she should not be obliged to do anything unless she wanted to. My plan was carried out, and it certainly was the happiest for her.

I did not worry about expense in those days, but soon had to. It was an extravagant way of living, with three houses, and moving about so often.

I hate to think of the mess we made of that house in Ennismore Gardens. The children were very rough and undisciplined notwithstanding Miss Hynde's and my efforts to tame them.

One day David sent Nelly and Miss Hynde to the dogs' home to find a dog for Nelly. They returned with a very ill-bred Fox Terrier. He really was a dreadful dog, and left his traces all over the house.

Charlie kept birds, paroqueets etc in a conservatory adjoining what we had to use as a schoolroom, but sittingroom of the lady of the house. Poor thing, she certainly found it much the worse for wear after our tenancy, but we paid up and she was quite willing for us to have the house again next year.

Charlie used to take his birds into the clothes-hamper to tame them, and he succeeded. One of the paroqueets escaped, and I believe I saw it later in the day, sitting on a balcony in Piccadilly.

We had a canary in the nursery which only used its cage to sleep in, and flew about the room all day. It used to go into the night nursery with David when he had his morning rest. One day in the Spring the canary flew out of the window and we saw him sitting near the top of a tall poplar in the Mews. The groom climbed up and caught him for us.

The house looked out into Brompton Churchyard. It does not sound cheerful, but it was very sunny and pleasant.

An old friend, Mrs Melhuish, came once or twice to stay with me at Woodslea. She had decided views on education, having had very little herself, and she told Miss Hynde that Charlie ought to learn to play the piano. Miss Hynde conscientiously did her best, but Charlie hated it, and one day said that he should run away, which he did from the door of Ennismore Gardens. I watched him from a window. He ran once round the square and then slipped into the house. I persuaded Miss H. to give up trying to teach him music. Rob was a dear little boy with innocent short-sighted eyes and beguiling ways.

Charlie went to Mr Hawtrey's school at ... at Easter. But I forgot to tell before that he had a pony in town called Paul, and one day just when we were sitting down to lunch, a policeman came to tell us that Charlie had fallen off his pony and had been taken to St George's Hospital. David went off to find him, and there he was sitting forlornly on the edge of a table and very glad to be rescued and taken home, very little the worse for his accident.

In the beginning of July Miss Hynde took Nelly and Rob to Southampton to live on David's yacht the "Gleam" so as to be out of the way when the baby arrived. I am afraid they had a very dull time in the "Gleam" in Southampton harbour. They could seldom induce the Captain to take them for a sail. David and his nurse went to Gorsey Hey.

On July 29th 1876, Annie was born in terribly hot weather. She was a beautiful baby, much better looking than David when he first arrived. Annie was christened at the church in Ennismore Gardens - poor Charlie sitting in a remote corner, being in quarantine for measles.

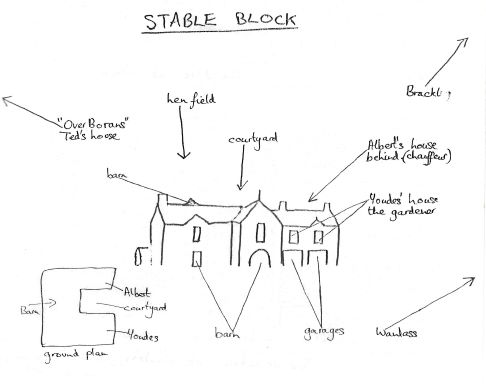

As soon as I was fit to travel we all went to Wanlass. How lovely it was to get there after London. The children always dashed in at the front door and out of the one into the garden. Dear Russell and Mrs Russell and handsome old Jenny Whittam were always waiting for us outside the front door. Russell and Jenny were our gardeners, and Mrs Russell took care of the house when we were not in it.

Russell had been in a shipbuilding yard. He did his best as a gardener and was faithfulness and straightness personified, and Mrs Russell was one of nature's ladies.

Our lives were a good deal cut up by our continual moves from one house to another. We loved Wanlass and made the most of our three months there.

David had started his new Company by this time. The "Tuscany" was the first ship; the "Thessaly", I think, the second. They began by going to India.

When Annie was about 18 months old David proposed that we should go for a voyage to Bombay in the "Thessaly". I don't think I ever thought of objecting, so we started off from Woodslea in a gale; David and I, the three older children, Miss Hynde, Annie and David and the undernurse, also Christy the sailor, who afterwards looked after and built our boats at Wanlass.

1877

David was 2¾ and Annie a year and a few months old. We drove to the Birkenhead Docks and all available members of my family came to see us off. Unfortunately it was blowing too hard for the "Thessaly" to get out of the dock, so they had to leave us to do our unpacking and settling in to our little deck cabins.

It was Christmas Eve, and the docks were a very dismal setting for it, the one redeeming feature being a pleasant and motherly stewardess who turned out a great comfort to us.

The "Thessaly" was essentially a trading steamer with iron decks and only a rail instead of bulwarks, and a small bit of wooden deck over the cabins.

Just when it was getting dark Mr and Mrs Laird very kindly sent to invite David and me to dine with with them. We went and enjoyed it, though driving back to the ship we felt (at least I did) rather an outcast, seeing everyone so busy buying their Christmas stores, holly, mistletoe, etc, and the brilliantly lit up shops. David, I am sure, was supremely happy.

We sailed early on Christmas morning. The cook made a bad start by coming on board the worse for drink and consequently cooking the plum pudding in salt water (perhaps Mersey), but I do not think it made much difference to most of us, as we felt disinclined for any plum pudding!

We had taken a young dexter with us, also a cow, and David being a G.W.R. director had a bright idea, namely the buying cheaply of an old third class railway carriage, which was fastened on to one of the hatches and very useful it was as a schoolroom and playroom for the children, also a music room for David and me. Many an hour did we spend in it, he playing the violin and I the piano, often feeling very seasick. I omitted to mention the piano.

We had a roughish voyage to Malta. We spent a lovely day there with old Mr and Mrs Maclver. She thought me quite mad to start off with the children on such a voyage in such a far from luxurious ship, and begged me to stay there, and let David go on by himself, but, of course that could not be, so I asked for some white loaves of bread and some good butter and off we went to Port Said.

We did not land there, but watched our ship and others coaling, with little men running up the gangways like ants, with coal in baskets on their heads.

The voyage through the Canal was deeply interesting with peeps of men and boys and women like Jacob and his family walking along with their flocks and herds. We saw a mirage too. When we stopped at night, the children wanted to get out and dig in the sand, but the Captain would not encourage it.

It was a wonderful peep into the East. We landed at Suez and were promptly forcibly mounted on donkeys and rode to the Hotel for lunch - much to the children's joy.

I think it was at Suez that David had a telegram calling him back for an important division. He hesitated, but decided not to go in the end. What he would have done with us (his family) did not bear thinking of. We should probably have had to go on to India without him!

We had news at Suez of Tuck's engagement to Ethel Perrin. They were engaged for five years before he could afford to marry.

It was rough in the Red Sea with a head wind and the lower deck was several inches in water, so the children were allowed to paddle in as few garments as decency allowed.

We passed a pilgrim steamer with yellow flag flying for Cholera. We saw the place where the children of Israel crossed. The African coast was jagged in the outline of its hills and dark and forbidding looking. It was hot and windy in the Red Sea.

The Captain very kindly gave up his deck cabin for me. I was feeling very seasick and miserable, but had to bestir myself when young David turned a tap somewhere under the sofa and deluged himself and the cabin with water!

On the whole the children were very happy, though young David did not like being hosed with the decks in the mornings. "Da-aavid does not like being hosed"!

Charlie and Robbie were as much at home on the sea as their Father, and Nelly used to sit in the cabin in broiling weather making a trousseau for her favourite doll, who was shortly to wed a very namby-pamby looking gentleman with no bones in his legs!

We had Nelly's dog with us, a beautiful fox terrier (not the London one!). He met with a tragic death in the Indian Ocean. Not being able to find any stones or bits of wood for us to throw for him, he picked up bits of cotton waste which we think he must have swallowed, because one day he had a fit, and the Captain brutally kicked him overboard, under the impression that he was mad. Nellie was inconsolable, and it cast a gloom over us all which did not pass until one morning we had our first sight of India in the distance.

We landed at Bombay and had a wonderful fortnight there staying at a Hotel, I think called the Esplanade.

David engaged a Parsee named Noroge Hiroge as our guide or Dubasha, and a very good one he was. Each morning after our Chota Hazre, (or early tea) we drove out through the Bazaars and saw a great deal of the real life of the town. One morning we were taken into the enclosure of a sacred tank and were regarded very unfavourably by the native priest.

One day Niroge asked if he might take little David and buy him a Parsee suit of clothes. We rashly said he might, and he was SO long in returning that I began to wonder what had happened. I think he must have taken David to visit his (Noroge's) relatives.

Rob had heard the Captain say that not more than half the price asked should be given for anything in India, so one day Rob, aged 8, came to the sitting room and proudly showed me several things which he had taken from a stall kept by a Hindu in the Hotel. He had put his money on the table and run off with the things, half price. I was telling him that he must take them back when the door opened and a turbaned head came round it. Rob was very crestfallen.

Noroge took us to see a Parsee wedding, or part of it, for the ceremony took, I think, 3 days to conclude. David and I had great wreaths of guelder roses thrown round our necks.

He and I went to Matheran for a weekend. We went by train and in the evening were carried up through the woods in tonous[?] or palanquins, the bearers either chanting or groaning over our weight all the way. Squirrels and monkeys were skipping about in the trees, and Tree Frogs innumerable, sounding like little bells ringing.

We stayed in a primitive hotel with a very wide matted verandah, with a lovely view of the ghats or rocky peaks. Only one other couple were there: a poor officer and his wife who had just lost one or two children from fever in the plains. She, poor soul, poured out all her sad history to me.

Luckily the children kept well while we were away. Only Miss Hynde thought she had cholera while David and I were at Matheran. No doubt she was promptly dealt with by Dr Boyle.

I think before finishing the account of the voyage, I ought to confess that in a fit of exasperation and temper I threw "The Hunting of the Snark" - a first edition - into the Indian Ocean because 1 was SO sick of hearing it continually recited by Nellie and her Father.

On the way back, we became firmly stuck, bow and stern, across the Suez Canal. Luckily it was evening, and ships did not pass through at night. So we had the whole night to get the ship right, and very hard work it was for the crew. The Captain lost his voice for a day or two through his strenuous shouting of orders.

The "Thessaly" had such a strong list while stuck that we could not lie comfortably in our berths on the upper side. I often wonder now what kept the cargo from shifting.

We arrived in the Mersey on March 13th, 1878. Soon after that Godfrey Hope died at Thurstaston on April 14th.

Maud Squarey was married to Tom Carver on May 1st this year. I do not believe there was ever a happier marriage than theirs.

End of First Part