Help for mothers

Correspondence around a letter to The Times in February 1943

The original letter, Feb 5th

My wife has just told me that a lady on the wireless has been stressing the importance of rest for nursing and expectant mothers, and of complete rest for those who have only been a fortnight in hospital. The speaker was absolutely right, but she must have been heard with some bitterness by the thousands of such mothers who can now get no domestic help of any kind. I heard yesterday of a girl in furnished rooms who was sent "home" with her baby after the usual 14 days (sometimes it is only 10): she had no help and the landlady went out to work, her husband is in the forces: the baby was heard crying persistently and, when a neighbour did go in, the mother was dead.

This is an extreme case, but I could quote too many cases where there is great and always harmful exhaustion. I understand that the W.V.S. and no doubt other bodies, are attempting to find voluntary help for the worst cases. There is, however, a further remedy that ought to be applied at once. Let the Minister of Labour state publicly that part-time domestic help for nursing and expectant mothers is a work of first class national importance, and let the exchange supervisors direct suitable women into this work. The child welfare clinics could tell them where to go.

I am, Sir, yours truly

GEORGE JAGER

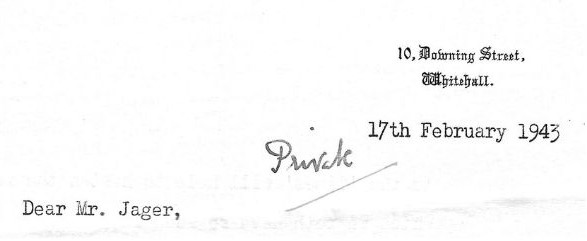

A reply from Mrs Clementine Churchill, Feb 17th

Thank you very much for writing to me.

I do not know that I personally

can be of much assistance as regards the part-time help which is needed by mothers before their confinement, and after they return home.

But I am going to ask Lady Reading's opinion as to whether it would be possible during the War for the Women's

Voluntary Services to help in any way.

I am

also going to try to interest the Ministry of Health and the Red Cross in opening post natal homes close to Maternity hospitals.

I so much hope that your letter

to the 'Times' will help to hasten the work

which we both have so much at heart.

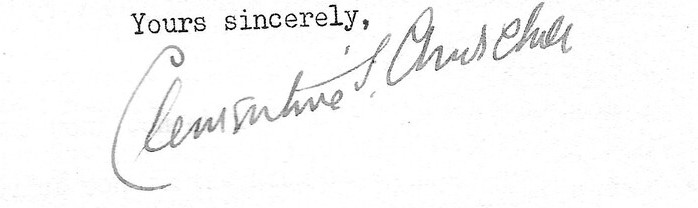

Mrs Churchill's letter published in The Times, Feb 8th

I have read with interest the letter in to-day's issue of The Times by the Rev. George Jager. After three years' experience gained at Fulmer Chase Maternity Hospital for the Wives of Officers, I endorse all he says. When our work started the hospital was not well known, and we could keep our patients for three or four weeks, but for a long time pressure on our beds has obliged us to discharge patients at the end of a fortnight after child-birth. The results compared with the first period were disappointing and sometimes pitiable.

A far-seeing philanthropist came to our assistance. By his generosity a roomy house near the hospital was bought, which, under the same direction, provides a post-natal home for our young mothers. Here patients stay for a another fortnight and learn to look after their babies and regain their strength. This addition to the maternity hospital has been of supreme value as countless letters from grateful girls and proud young fathers testify.

Is not the next step forward in maternity treatment the establishment of post-natal homes in connexion with all maternity hospitals? It is possible that experienced mothers may not need such a place, but for the young mother with her first baby we believe it to be an essential part of maternity and child welfare work.

Your obedient servant,

CLEMENTINE S. CHURCHILL,

Chairman of the Council,

Maternity Hospital for the Wives of Officers in the Royal Navy, Army, and Royal Air Force.

10, Downing Street, Whitehall

Further letters to The Times

Mr. Jager, of Birmingham, raises the problem of help for mothers in his letter published in your issue to-day. The Ministry of Health issued a circular to maternity and child welfare authorities on November 23 dealing with the question of home helps which was the result of careful scrutiny of this problem by the Advisory Committee on the Welfare of Mothers and Young Children.

This circular points out that after representations from the advisory committee, the Ministry of Labour agreed to recognize the work of home helps as work of national importance and has circularized its local offices authorizing them to submit women between the ages of 40-45 to welfare authorities for this work (as being the most suitable age group). Welfare authorities were further requested to review their present home help services with a view to developing them to meet the very real war-time needs.

The response to this circular has been, I understand, patchy, but the question is not one which has been ignored. In areas where there is a deficiency in the local home help services, representations should be made to the welfare authorities who, in cooperation with the employment exchanges, should be able to provide the necessary personnel. It is indeed distressing to read of yet another instance where the existing machinery is evidently not being properly used and hardship, and even suffering, being unnecessarily endured by the mothers of this country.

Yours faithfully,

BEATRICE WRIGHT

House of Commons

Two letters published in to-day's issue of The Times deal with problems that cause so much anxiety to mothers in this large residential area that I hope you will allow me to enlarge upon them. My own case is typical of that of many other housewives.

I have a six-month-old baby and a child 4½ years old, and as I can obtain no domestic help my working day is one of 16 hours for seven days a week. The shopping centre is 30 minutes' walk away, and the school my daughter must shortly attend is 35 minutes' walk away and is remote from my shopping district. No police supervision is provided at a busy traffic crossing, and small children must venture alone or add to their mothers' overburdened day the extra fatigue of escort duty. The local education authorities, having decided against building a school for the many children here who need one close at hand, refuse to provide a conveyance to take children to the distant council school, or even to discover by means of a questionnaire how many parents in the area would send their children to a State school if a conveyance were provided.

Faced with the prospect of sending little children, in all weathers, such long distances and of exposing them to traffic dangers if unescorted, many parents send their children to local private schools, though as taxpayers they feel bitterly the lack of understanding which deprives their children of that democratic education which is generally agreed to be one of the ideals for which in this war we fight and strive.

Yours truly,

MURIEL GOODALL

15, De Vere Walk, Cassiobury, Watford, Herts

All engaged in maternity work must be interested in this subject raised by the Rev. George Jager and the practical suggestion made by Mrs. Churchill.

Before the last war it was difficult to focus public attention on the needs of a maternity service; since then the public have become more and more obstetric-minded, and it is surely not too much to hope that Mrs. Churchill's advocacy of this much needed extension of our maternity services will soon bear fruit.

Yours sincerely,

WILLIAM FLETCHER SHAW

I welcome Sir William Fletcher Shaw's suggestion that all mothers should be given a fortnight's rest following confinement in order that they may recuperate, and at the same time learn to manage their infants without being harassed with family responsibilities. Although our scientific knowledge has increased enormously during the last 100 years, we are slow to apply it to the needs of the expectant and nursing mother. She is still expected in the majority of homes to be up and about on the tenth day after childbirth and ready to tackle the chores, although we know that if she is to nurse her baby successfully she should have adequate rest.

The war-time mother should have special consideration. Not only is she subject to the stress of the exigencies of war but during her pregnancy she is too often a prey to anxiety concerning the conditions under which she is to be confined. It is startling to learn that during the last three months of 1942 more than 2,000 expectant mothers had to be turned away for lack of accommodation from the 30 voluntary hospitals with maternity departments in inner and outer London. The physical and mental suffering of these mothers and others like them in all parts of the country should be a matter of concern to all who are interested in maternity and child welfare. The maternity grants which are proposed in the Beveridge report will fail to encourage women to have children unless the community comes to regard childbirth and the after care of the mother as of primary importance to the State.

Yours sincerely,

EDITH SUMMERSKILL.

House of Commons.

There are at present in this country over 200 auxiliary hospitals, convalescent homes, and residential nurseries, with a total bed complement of well over 12,000, provided by the Joint War Organization of the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John by arrangement with the Ministry of Health. All of them are admirably equipped and staffed for their particular purposes in war-time, and the bulk of the cost has fallen upon public funds. They are distributed among all the counties of England and Wales and thus conveniently accessible to our large and small towns. Many of them are adapted mansions and are unlikely to be occupied again as private in residences. Would it not be possible after the war to link up many of these eminently suitable auxiliary hospitals and convalescent homes with our maternity hospitals and maternity units in general hospitals for the purposes advocated is by the Rev. George Jager, Mrs. Churchill, and the President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists?

Yours faithfully,

FREDERICK MENZIES.

Bronnant, Criccieth, N. Wales,

I hereby support all that has been put forward by you, Mrs. Churchill and Sir William Fletcher Shaw, with regard to the necessity for the provision of convalescent homes for mothers and babies after leaving hospital. Most young mothers are unfit to cope with the care of the first baby and to look after the home, especially when their residence in hospital may be limited to eight or 10 days owing to the pressure upon maternity beds. A fortnight's residence in a convalescent home makes all the difference in the after-care of the mother and child.

It has been found that most mothers do not wish to stay longer in a convalescent home than two weeks as they are anxious to get back to their own homes and relatives. The characteristic of British women is a preference for their own home and possessions no matter how small and meagre. What is urgently wanted is more consideration from the local health authorities for better housing facilities for mothers and babies, and the provision of home helps to enable them to maintain a condition of health. If women had some help in their homes, or could leave their babies for an hour or two in a day nursery while they went shopping it would relieve a great deal of their anxiety. Most day nurseries do not admit babies under nine months of age. The difficulties which face the young mothers of all classes are great owing to the shortage of help in the home. We can only admire the courage which sustains them while carrying on this greatest contribution that can be given to the State.

Yours truly,

A. LOUISE MCILROY,

Chairman, National Council for Maternity and Child Welfare.

117, Piccadilly, W.1.

Subsequent correspondence

Dear Sir,

A copy of a letter written by you to the Times on February 14th has been forwarded to me by a certain Miss Chadwick, living at Canford Cliffs, Dorset. Miss Chadwick lived on Merseyside for many years and she therefore knew of the Service of Home Helps, which has been run by our orgainsation since 1920. She wrote to ask if the Service was still in existence. In reply, I gave her particulars of the Service which we are still running, and in view of your letter, you will, I think, be interested to hear the details yourself.

I therefore enclose a copy of the letter addressed to Miss Chadwick, for your information.

Yours faithfully,

Jessie Beavan.

Hon. Secretary.

Women's Service Bureau

9, Gambier Terrrace, Hope Street, Liverpool 1

Dear Madam.

The Secretary of the Personal Service Society has forwarded to me a letter received from you a few days ago, enclosing a letter which appeared in the Times on February 5th.

Your recollection of a service of Home Helps in Liverpool is quite correct. This service was started by the Women's Service Bureau in 1920, and was really the outcome of the experience gained by our Maternity Department which throughout the 1914-1918 war, and ever since those years, has provided Maternity Outfits for expectant mothers, whose circumstances made it impossible for them to make necessary provision for themselves. Our contact with these mothers made us realise the need of women of domestic experience, who could look after the children, keep the home going etc. during the mother's confinement and during convalescence, whether her baby was born in hospital or at home.

We made a beginning in 1920 with two Home Helps and the number steadily grew until in the year preceding the war we had sixty women on the permanent staff and twenty extra women for emergency use. Enquiries from other towns proved that our service was by far the largest in the Country.

The women, at that time, received £1-1-0 per week and a retaining fee of 14/6 when not working, and the families served contributed according to their means. In very exceptional circumstances a Home Help was occasionally sent free of charge.

I much regret to say since the outbreak of war the service has diminished and that we now have only twenty-two women on the staff. Some of the younger women felt that they ought to volunteer immediately for one of the Services, and even the older ones were approached by the Ministry of Labour and it was only with extreme difficulty and after much argument that I succeeded in obtaining exemption for them. Two months ago, after 3½ years of war, we were informed that the work of the Home Helps could be regarded as a "reserved occupation". This news reached us when we had lost most of our women. Those who have remained are doing wonderful work and personally I feel that no form of war service could be more valuable.

Although we have increased the salary of the women to 30/- per week, working or not working, even this increased amount compares, as you will realise, most unfavourably with salaries paid to women at the present time, and I think it is only love of their work and a high sense of duty which has induced the twenty-two, who are still with us, to carry on.

It is quite true that the payments of families, in many cases, were only slightly less than the actual salaries paid to the Helps, but of course, there are many administration expenses and we could not have maintained the service without a Grant from the Ministry of Health and voluntary subscriptions.

I think that I will send the information which I have given in this letter to the writer of the letter sent to the Times, as he will probably be interested to know that such a service is actually in existence.

I shall be delighted to supply any further information, should you wish to have it.

Yours faithfully,

JESSIE J. BEAVAN.

Hon. Secretary.